Opening chord – recycling – objective knowledge – I sell my soul – a scientific experiment – the oldest cliché – formulaic language – undeniable facts – Faust – problems of translation – the meaning of words – tea break – DNA – active inference – statistical exploration – “in the wild” – life itself – participant observation – digression – rule-breaking – recursion – “the quantified self” – proxy measurements – homeostasis – existence – representation – brain scans – evolution – Help! – The Good Regulator – incomplete incompleteness – confidence – brainwaves – abstractions – a better misunderstanding.

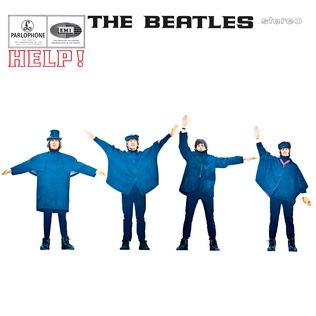

In the beginning there was magic. It began with the opening chord of A Hard Day’s Night and spiralled beguilingly across two sides of vinyl until the fading notes of I’ll Be Back.

If you don’t find this interesting, read on.

They say vinyl is making a comeback. Everything gets recycled in the end. Younger generations have rediscovered the pleasure of record players, rescuing their parents’ collections from garages and lofts. The first LP I ever bought, before the oil crisis, was the Beatles’ fifth: Help! It was the most beautiful thing in the world, at the time.

I was unaware till recently – objectively, how could I have known back then? – that my friend’s dad had been on the other side of the Atlantic and brought back the American version of Help!, which, unlike the British one, interspersed songs from the film with instrumental numbers from the soundtrack, featuring the first use of a sitar on their records and – interestingly – inspiring George Harrison to learn the instrument well enough to play it on Norwegian Wood on their next album, Rubber Soul.

I can’t pinpoint the moment precisely – and just as well, because if I had tried to, it may never have occurred – but somewhere between Help! and A Hard Day’s Night, spanning the records and the films, between the Beatles, producer George Martin and director Richard Lester, I sold my soul to pop. “It’s so fine, it’s sunshine.”

If this essay was a scientific experiment – which it is – it would be an experiment in how interested you can be in something you are never going to find interesting. Read on.

The classics were a closed book to me, a mystery without the thrill of pulp fiction. Why should I care if the rosy fingers of dawn in Biggles books were the oldest cliché in Western civilisation? It’s how you use your clichés that matters and eventually, I had to admit – ruefully – as I grew out of my teens, Captain W E Johns piled them high and sold them cheap. He wasn’t even a Captain.

A renewed effort to study English Literature, however, was doomed almost from the beginning. How could Anglo-Saxon fondness for a formulaic phrase – with a ring-giver waiting for you at every mead-bench – really compete with Afternoon Tea by the Kinks?

Pop often – it’s one of many undeniable facts we have to take on trust – sells the illusion to its listeners that, even in the midst of a crowd, this song is about you. But I am the evidence. By the time, on Rubber Soul, the Beatles sang The Word, they were aiming straight at my heart:

Everywhere I go, I hear it said,

In the good and the bad books that I have read…

Now I’m older, perhaps it’s even truer than it was then. I’m still looking for answers in all the wrong places, but occasionally I get a good book recommended to me. Recently, it was Goethe’s Faust. In this scene, he opens the Bible on John’s Gospel:

It says: “In the beginning was the Word.”

Already I am stopped. It seems absurd.

The Word does not deserve the highest prize,

I must translate it otherwise

If I am well inspired and not blind.

It says: In the beginning was the Mind.

Ponder that first line, wait and see,

Lest you should write too hastily.

Is the mind the all-creating source?

It ought to say: In the beginning was the Force.

Yet something warns me as I grasp the pen,

That my translation must be changed again.

The spirit helps me. Now it is exact.

I write: In the beginning was the Act.

Is that as good as Afternoon Tea? Perhaps it loses something in translation (by Walter Kaufmann, from the German). But it does raise an interesting question: what kind of word was John Lennon thinking of, when he sang, “the word is love”? He was married but not exactly happy. Norwegian Wood is supposedly an obscure retelling of an extramarital fling. And now I’m wondering if Afternoon Tea ain’t the same: a euphemism for Something Else in Ray Davies’ wandering mind…?

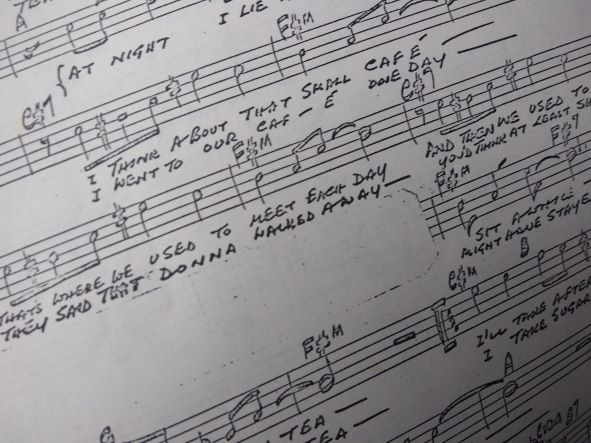

Teatime,

Still ain’t the same without m’ Donna.

At night,

I lie awake and dream of Donna.

I went to our café, one day.

They said that Donna walked away.

You’d think at least she might have stayed

To drink her afternoon tea.

It wouldn’t be the first song to wave its spoon in that direction. Need a Little Sugar in My Bowl, lamented Bessie Smith in the Thirties.

Now it’s time to stir in a little science. Essentially, words are the same as individual cells in an animal or plant, apart from the DNA, of course – although some would argue that words are living things containing their own kind of DNA.

Like living things, words have boundaries separating them from their environment. And the living thing within the cell wall – within the crisp outline of the word – becomes a model of its surroundings, through a process that leading theorists often refer to as active inference.

Of course, we shouldn’t be too literal about this. The word Help! is not the pixels on the surface of a screen, nor the ink bleeding into the fibres of a sheet of paper, nor is it the succession of sound waves entering your ear. Nevertheless, what the best theories are telling us is that every living thing – wherever and whatever it may be – is constantly learning about the world, statistically, by exploration.

How does it do this? This is where the science is less certain. A word, or an individual cell in the human body, is not going to learn the rules of table tennis, for instance. However, it will learn information that is relevant to its own survival as it interacts with the world. A cell is, of course, highly dependent on its support mechanisms in the rest of the body. Once separated from this, it will not survive long “in the wild”. The same is true of a word. When spoken, it soon disperses in the air without listeners to catch it. It can linger for centuries on a page in a humidity-controlled library, but requires readers familiar with the language of the time to interpret whatever that word discovered on its travels.

There are an increasing number of Machine Learning algorithms being run in laboratories on energy-hungry computer processors, competing in research papers to produce the best results against a set of benchmark tests. These aim to approximate ever nearer to how cells – or words – really work. The challenge is for the maths to get beyond an interesting approximation and provide an insight into the mechanisms of life itself. For this, it must find a way of entering into the life of the mechanism, recording measurements of bodies on the move, over time, as a participant-observer.

A moment’s introspection reveals how hard this is. If you think about how you’re breathing, in and out, concentrate on it, within a few seconds you’re no longer breathing quite as naturally or unselfconsciously. The act of measurement subtly skews the results.

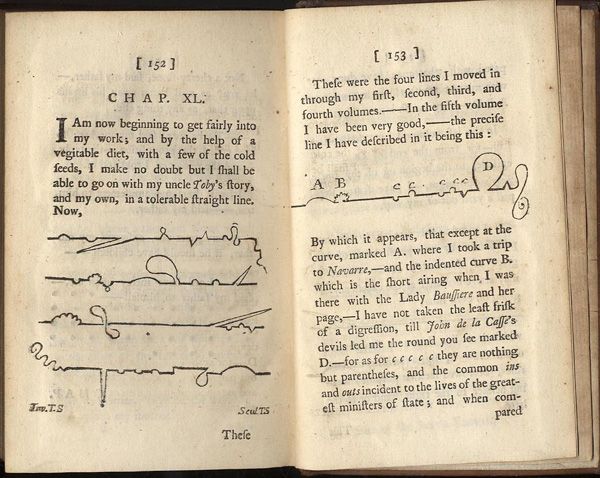

And there is no end to what we can measure – best illustrated by a short digression – and what better to illustrate a short digression than The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy?

In retrospect, the University’s forbearance in persisting with my education wasn’t a total waste of everyone’s time, it did introduce me to a consumptive vicar who, two hundred years before Help! (the movie), was already determined to break as many of the rules as possible before they could all be written.

While the author begins his life story conventionally enough, at the beginning – in the middle of the act of his conception – the problems of writing intrude constantly and it becomes clear that there is no chance he will ever finish his recursively intractable endeavour.

There is a modern echo of this wilfully futile undertaking in the activities of lifeloggers, clocking up reams of data about themselves – “the quantified self” – beyond any sensible limit of interpretation. But what if they’re not keeping track of the right things? Shouldn’t they also be monitoring what they’re monitoring? ‘Cause if they don’t, how can they ever tell if any of it was really worth it?

Many of us, with more guilt than ambition, intermittently watch our weight or what we eat, whether as a vain proxy for our general state of health or simply so we can continue to fit in the clothes we own. We hit on a variable and hope to control it, as long as we can.

Homeostasis, or staying within our limits, may also be achieved less self-consciously as we play our part in the games of life, by embodying a predictable tendency to engage in all the usual kinds of things rather than skittering off in random directions, digressing to the point of almost disappearing from the page… . . . . . . . . . . . .

The word Help! is lifeless on its own. It achieves life through its encounters. When we first encountered the word, it was already in existence, it already had meaning. In the beginning was the word, if we can only find where it began.

When I bought the LP, it began, for me, to represent the album cover, the Beatles’ faces, the glossy shades of blue on the front, the black and white typography and halftone images on the back. It was the weight of the record in my hand, the sound of the needle settling into the groove, the length of the pauses between the tracks…

I can see you thinking – I can imagine you thinking – “But that isn’t what ‘help’ means!” Not to you, maybe. You had to be there. And, I promise you, you have been there for all your encounters with the word ‘help’, or Help! The word itself learns from all these fleeting acquaintances. It doesn’t exist in stark isolation on an album cover, in the quivering air, on a library shelf. It is more uncertain than that. It won’t be pinned down to a single pixel; no molecule of ink; no frozen movement of the tongue; it isn’t contained in any one brain cell, a whole brain scan, or the people in any one city. It is older than you, and it will outlast you.

Where did it begin? In the Mind, the Force, the Act? If the act was a whole play, it wouldn’t encompass all of the beginnings of the word. It didn’t begin with a big bang: it evolved, in the midst of a mess of evolution, slowly, immeasurably. The same difficulties in measuring recur with any living cell. Whatever scientific instruments we employ, there will be some part of a cell’s life we have decided not to measure or otherwise failed to account for; an overflow, uncontained by any model. Perhaps this doesn’t matter, but we have to be aware of our choices and our omissions. Can we finally ever have said enough?

The life of the word Help! depends where it finds itself from day to day and what we do with it. It is a living thing: it can save our lives, in the right circumstances, not on its own but… given a little help.

A living cell may, across its fragile membrane, engage with the world using active inference or similarly robust modern scientific theories; while the world, with all the resources of the solar system, will be applying itself with equal rigour right backatcha to that cell. The Good Regulator Theorem, conceived by Roger C. Conant and W. Ross Ashby, proposes that “every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system”. I do believe this is in some sense true. A model assumes the presence of a much larger world, a world which – however hard it tries – can never wholly fit itself back into its model. Complexity multiplies permutations of partial, mutual and missed interpretations.

There must be a theory somewhere that allows us to quantify the difference between our theoretical models of all this endlessly incomplete mutual modelling that everything gets up to in real life and the actual incompleteness of all such attempts, ours and theirs.

We could then use this number to reduce our confidence, with precision, in the confidence of mathematical modellers. Until then we can only guess…

Rereading this – before you’ve quite finished reading it – I’m conscious of an absence, when I compare the brainwave I had – or thought I had – to the ripples produced in this little essay: the difference between an idea and its execution. The idea in its perfect form told the story of the word Help! – fractal and emergent, shape-shifting in pulses throughout human history, in episodes of the everyday, leaving audible and visible marks on our culture and, more obscurely but with no less reality, in the cells of our very being. And then… and then we would try to picture how a mathematical formula sees it. To see what it doesn’t see, what the writer of the equations does or doesn’t see. And now I’ve written something falling short of that… but in sharing that failure, at least I’ve made the most of my free energy.

The complications of language began as soon as we opened our mouths. And the ramifications of reification are almost endless. Abstractions dance towards definitions, turning with a little fancy footwork into figures of speech. Numbers seem to reveal the secrets of the universe while exposing the eternal incompleteness of number systems. We pack concepts we don’t fully understand into words we think we have a handle on. Information. Life. Evolution. You name it. Somewhere along the line, a general theory of everything ends up as a particular instance of something and, if we stop paying attention, we trip over old intellectual baggage. What else is new? There’s no magic formula.

In the beginning, I misunderstood,

But now I’ve got it, the word is good.